MILTON LAND LAB 2022

Final Projects

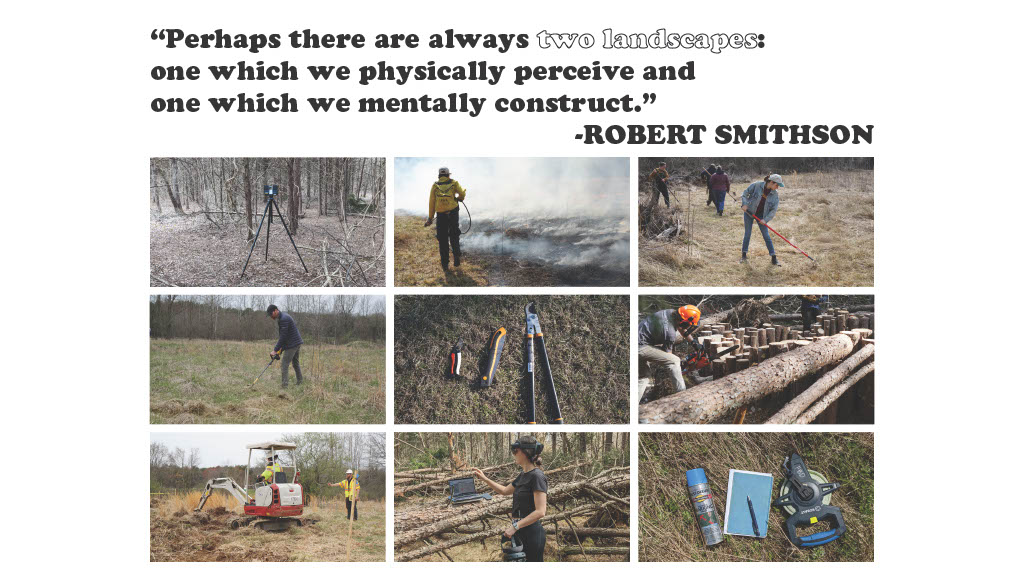

As a foundational epistemology to probe, the studio tasks students with researching and designing a mesocosm investigation to construct, observe, and document over the spring semester.

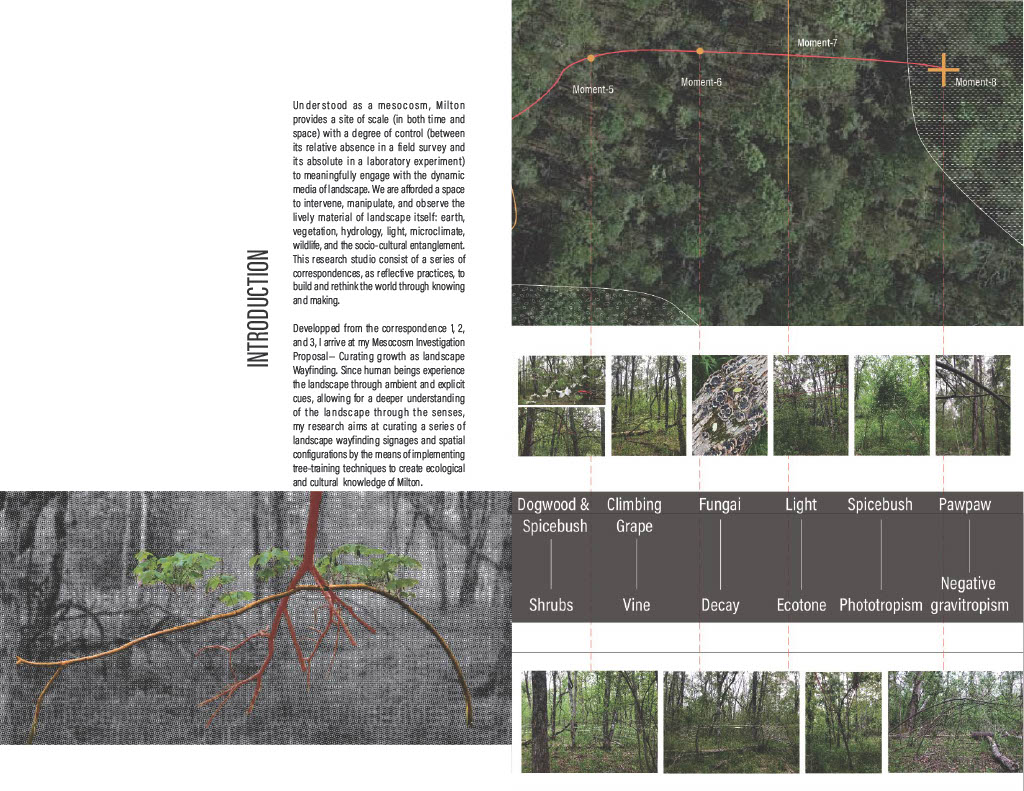

Understood as a mesocosm, Milton provides a site of scale (in both time and space) with a degree of control (between its relative absence in a field survey and its absolute in a laboratory experiment) to meaningfully engage with the dynamic media of landscape. Whereas an architecture school’s often ubiquitous fabrication lab affords a place to fabricate with largely static media, we now are afforded a space to intervene, manipulate, and observe the lively material of landscape itself.

Understood as a mesocosm, Milton provides a site of scale (in both time and space) with a degree of control (between its relative absence in a field survey and its absolute in a laboratory experiment) to meaningfully engage with the dynamic media of landscape. Whereas an architecture school’s often ubiquitous fabrication lab affords a place to fabricate with largely static media, we now are afforded a space to intervene, manipulate, and observe the lively material of landscape itself.

This not only provides space and time at scale, but, crucially for this studio, it provides opportunity to investigate a plurality of ways of knowing, with the potential to cultivate alternative worldviews and paradigms of landscape architectural practice.

Building on the reflexive practice of the previous correspondence assignments, the mesocosm investigation is one of durational feedback between intervention, observation, and evaluation, subsequently informing intervention anew. The following are students’ final projects, a culmination of semester’s material explorations.

Building on the reflexive practice of the previous correspondence assignments, the mesocosm investigation is one of durational feedback between intervention, observation, and evaluation, subsequently informing intervention anew. The following are students’ final projects, a culmination of semester’s material explorations.

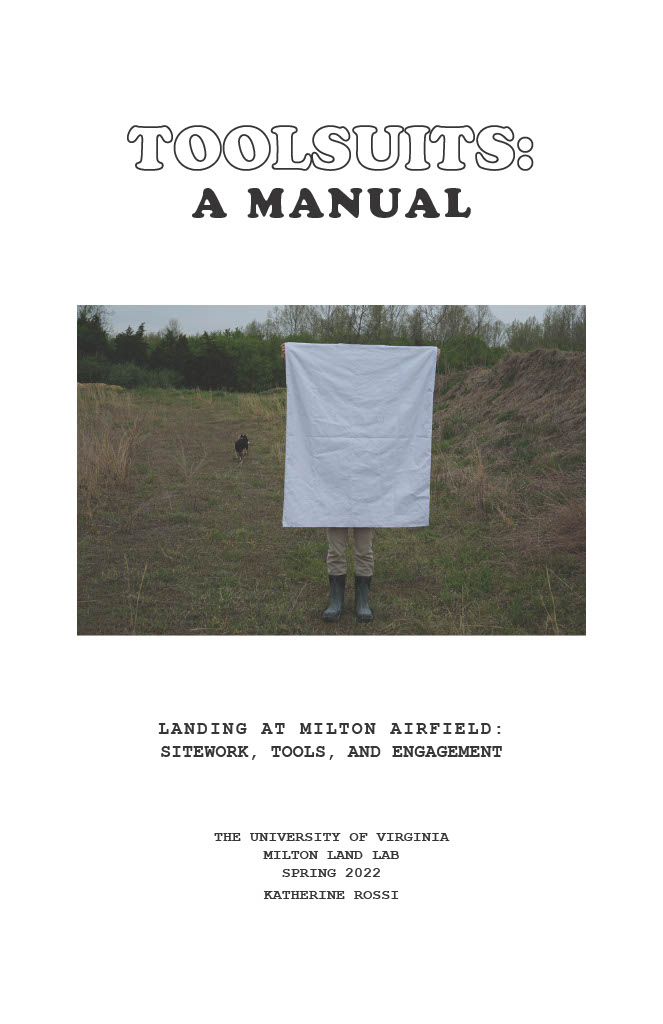

Katherine Rossi’s

LANDING AT MILTON AIRFIELD:

Sitework, Tools, and Engagement

LANDING AT MILTON AIRFIELD

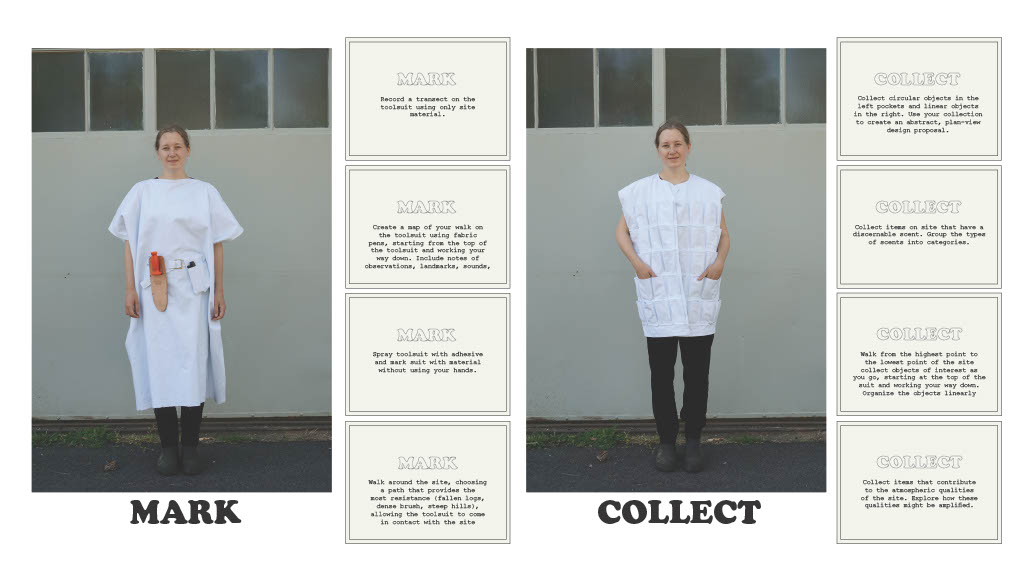

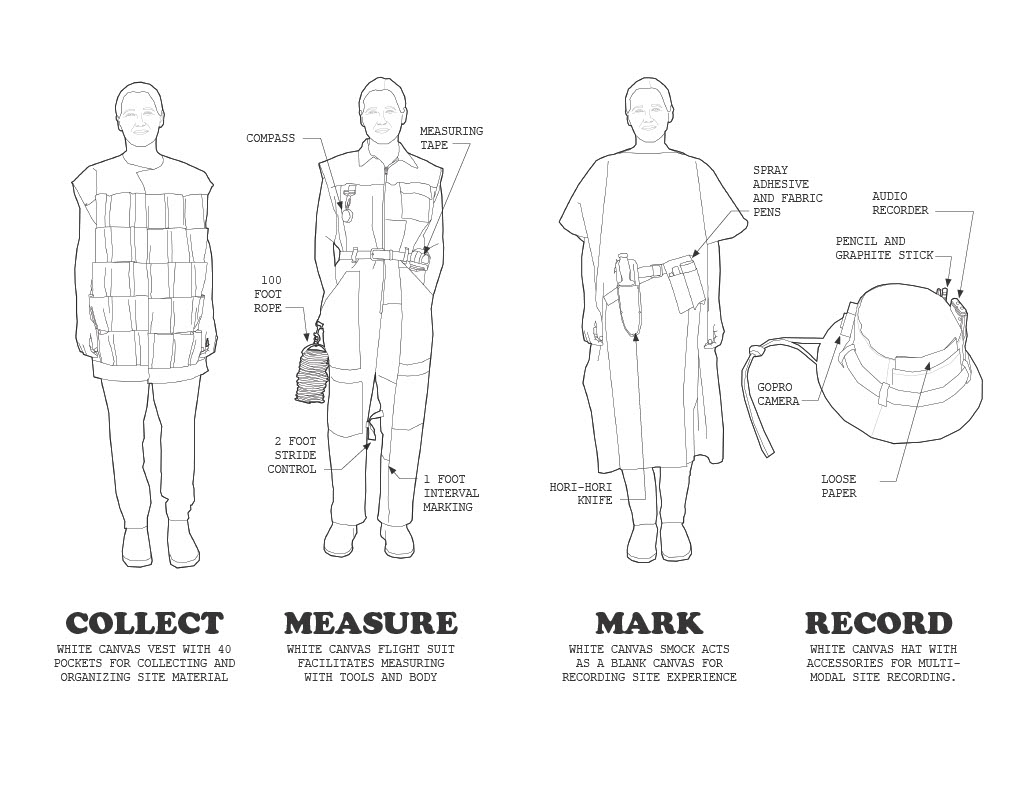

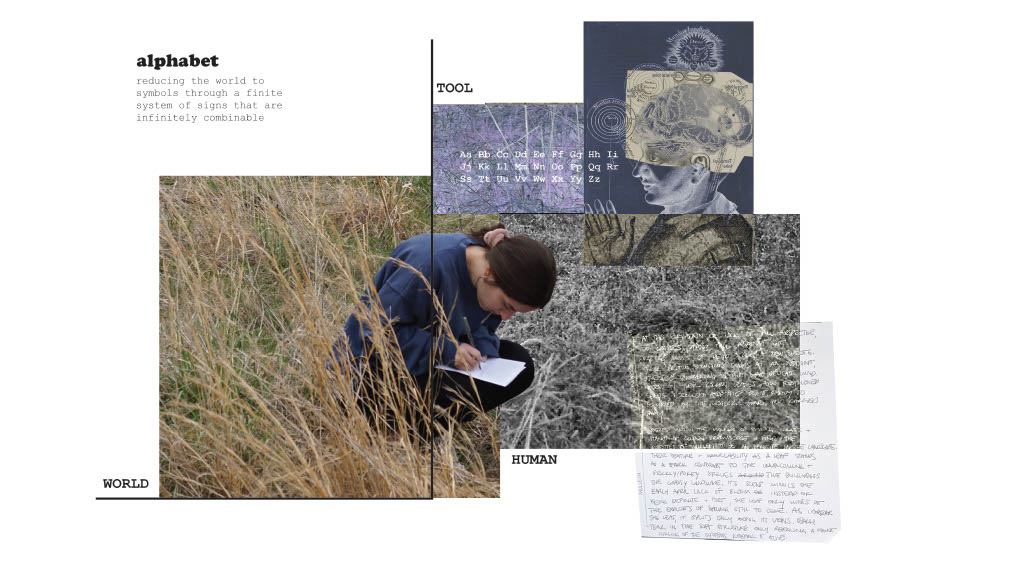

The tools we use as designers for conducting sitework are non-neutral and embed certain assumptions into the land. Landing at Milton Airfield interrogates sitework tools through a phenomenological lens to understand how tools function as intermediaries between our body and the land and the ways in which this interaction shapes our perception of the site. Sitework tools vary in technological complexity and require different levels of mental engagement and physical presence. Tools also vary in the way in which they relate to the human body and the world - tools can be embodied, read, or interacted with. It is important to recognize how tools condition the way in which the designer views the site and conducts site research.

Throughout the semester, I have experimented with different types of tools and forms of sitework, developing an understanding of the tool’s role in mediating and recording the site and shaping my body’s relationship to it. This experience led to the creation of three “toolsuits” that are designed to engage designers with the site in an embodied and specific way while extending time spent on site. The toolsuits are a compact, and wearable fieldkit that directs the wearer’s actions towards embodied sitework. Toolsuits are meant to be speculative and generative, encouraging the wearer to slow down, reflect on the site, and record it in a site-specific way while developing novel and corporeal methods of working and engaging with the site. The toolsuit becomes a vehicle for organizing site material and generating future design interventions.

Throughout the semester, I have experimented with different types of tools and forms of sitework, developing an understanding of the tool’s role in mediating and recording the site and shaping my body’s relationship to it. This experience led to the creation of three “toolsuits” that are designed to engage designers with the site in an embodied and specific way while extending time spent on site. The toolsuits are a compact, and wearable fieldkit that directs the wearer’s actions towards embodied sitework. Toolsuits are meant to be speculative and generative, encouraging the wearer to slow down, reflect on the site, and record it in a site-specific way while developing novel and corporeal methods of working and engaging with the site. The toolsuit becomes a vehicle for organizing site material and generating future design interventions.

The toolsuits were created to empower designers to interrogate their tools and resulting fieldwork methodologies and encourage experimentation and personalization. The toolsuits force designers to approach their fieldwork with creativity and individuality with the goal of expanding their methodological practices while creating new landscape aesthetics and ways of knowing.

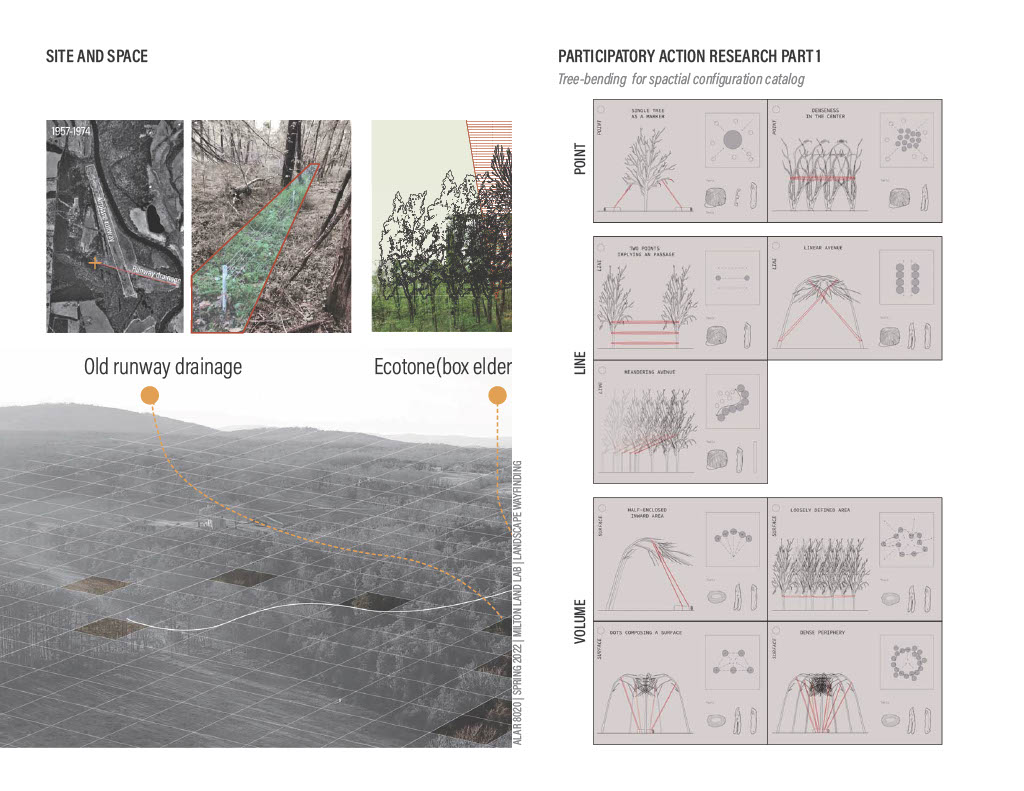

Youfang Duan’s LANDSCAPE WAYFINDING: Curating Growth as Landscape Wayfinding

LANDSCAPE WAYFINDING

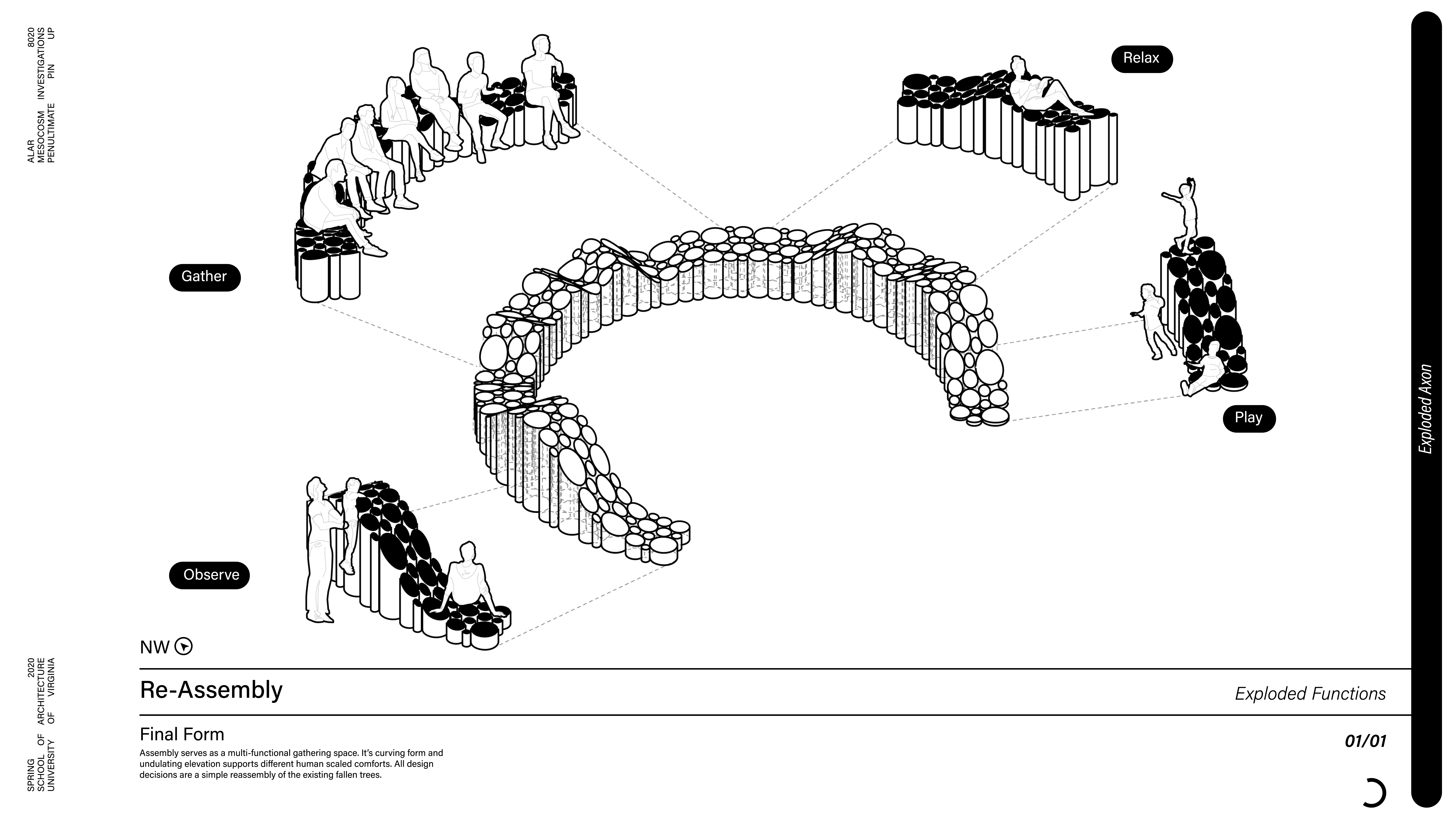

Alex Hall’s ASSEMBLY: Intervening in Spatial Ecologies Following Disturbance

The structure of the forest is spatially indeterminate and physically transitional, particularly after experiencing a substantial disturbance. After storm events, existing forest structures are often drastically altered and leave behind a chaotic conglomerate of undefinable spaces. Despite this, there lies an opportunity to respond to the wreckage area with a focused intention. The project responds to this found landscape and produces a refined interpretation of the fallen forest structure. By taking into account the respatilized ecology first, the site is the ultimate force behind design decisions. Subsequently, using the reassembled forest as a foundation, human-scale takes over as the primary design driver.

Within the chaotic conglomerate of storm debris, anarchy ruled in a beautiful way. However, through repeated physical exploration and digital modeling of the tangle of fallen pine stand, both form and function were slowly uncovered. Certain influential elements and spatial characteristics were then selected from the disturbed site and gave direction to the forest re-assembly.

Within the chaotic conglomerate of storm debris, anarchy ruled in a beautiful way. However, through repeated physical exploration and digital modeling of the tangle of fallen pine stand, both form and function were slowly uncovered. Certain influential elements and spatial characteristics were then selected from the disturbed site and gave direction to the forest re-assembly.

ASSEMBLY

Linnea Laux’s MILTON RIVER LAB

Flooding and Ways of Knowing

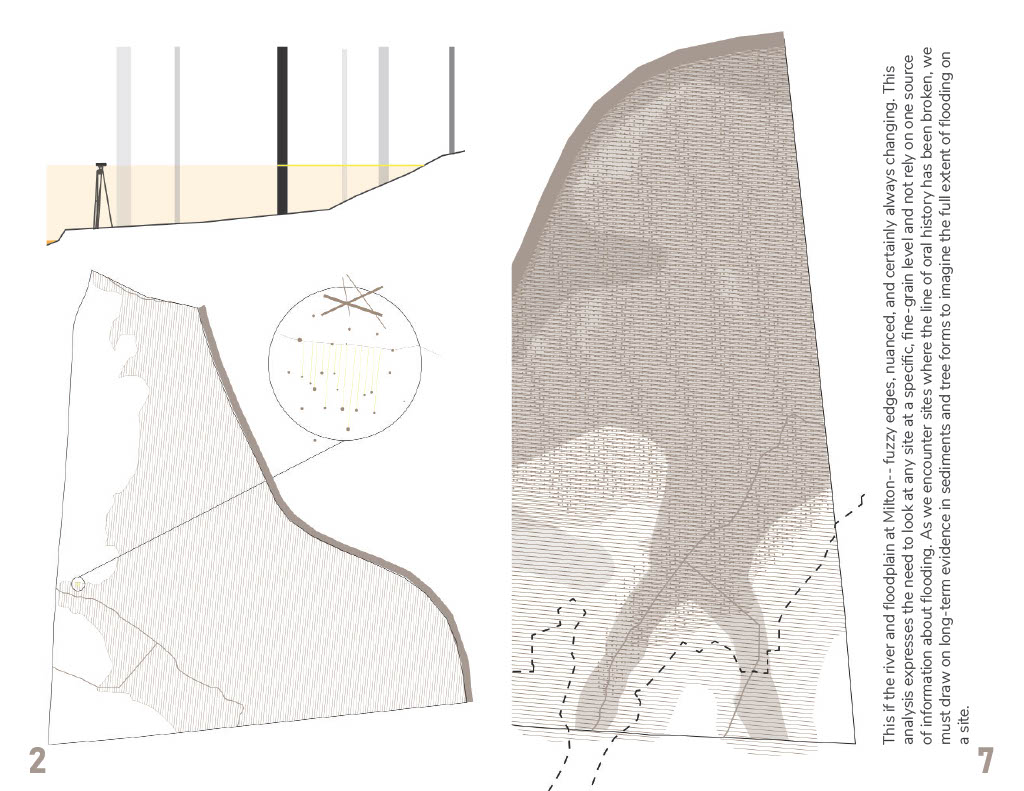

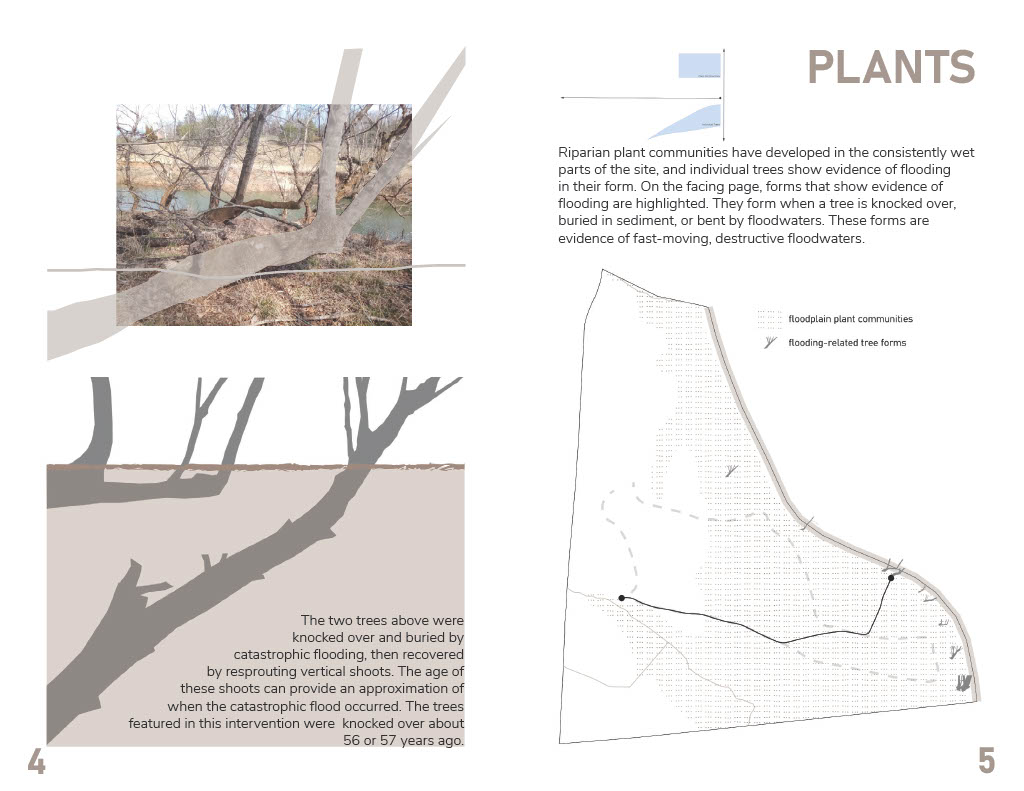

On the first day of class, Matthew showed us a map of Milton with only an aerial and the 100-year floodplain line. I was immediately curious about this line, and whether it could be felt when moving through the landscape. I started to explore changes in soil through Correspondence 1, built little dams on the streams in Correspondence 2, tried to characterize the microtopography at the meeting point of the streams in Correspondence 3, and then settled on exploring alternative sources of evidence about flooding in correspondences 4 and 5. I was limited to the sources of information I could access with my tools and skills, but was still able to map and synthesize botanical, soil, and historical information about flooding. I probably explored ten ideas for literalizing this information in the landscape, but finally settled on painting trees to show their flooded forms, using rope and bungee cord to re-create the water level of a past flood, and putting soil swatches keyed to a map in a booklet to demonstrate the variety of upland and riparian soils on the site.

My project essentially explores multiple “ways of knowing” about flooding at Milton. I had expected to be comparing evidence from plants and plant communities, stories, and soil to the historical record, but I found that the record is much spottier than expected. Continuous data is available for less than the past year, and past gauge measurements mainly focus on flood events. My project ended up being a synthesis of botanical, soil, and historical evidence of flooding.

I think that a lot of our ill-advised decisions around “flood control” in the United States stem from the way that we imagine water, land, and floodplains. We create, both through lines on maps and built interventions such as levees, “safe” and “unsafe” zones that are mostly binary and do not change over time. At the same time, we have lost (murdered) or ignored a lot of the ancestral knowledge that could have helped us make better decisions at a local level. Many people and designers live and work in places where they do not have family history. How can they quickly gain an intuition for flooding, and communicate that to others, even without automatic access to an oral tradition? The 100-year floodplain will continue to exist and affect insurance and regulations, but it should not be our first or only source of information about where water may go in the future. Modeling, storytelling, and observation of the evidence on a site must be synthesized to create a nuanced understanding of a flooded place.

My project essentially explores multiple “ways of knowing” about flooding at Milton. I had expected to be comparing evidence from plants and plant communities, stories, and soil to the historical record, but I found that the record is much spottier than expected. Continuous data is available for less than the past year, and past gauge measurements mainly focus on flood events. My project ended up being a synthesis of botanical, soil, and historical evidence of flooding.

I think that a lot of our ill-advised decisions around “flood control” in the United States stem from the way that we imagine water, land, and floodplains. We create, both through lines on maps and built interventions such as levees, “safe” and “unsafe” zones that are mostly binary and do not change over time. At the same time, we have lost (murdered) or ignored a lot of the ancestral knowledge that could have helped us make better decisions at a local level. Many people and designers live and work in places where they do not have family history. How can they quickly gain an intuition for flooding, and communicate that to others, even without automatic access to an oral tradition? The 100-year floodplain will continue to exist and affect insurance and regulations, but it should not be our first or only source of information about where water may go in the future. Modeling, storytelling, and observation of the evidence on a site must be synthesized to create a nuanced understanding of a flooded place.

Dina Luo’s

LANDSCAPE MARKING:

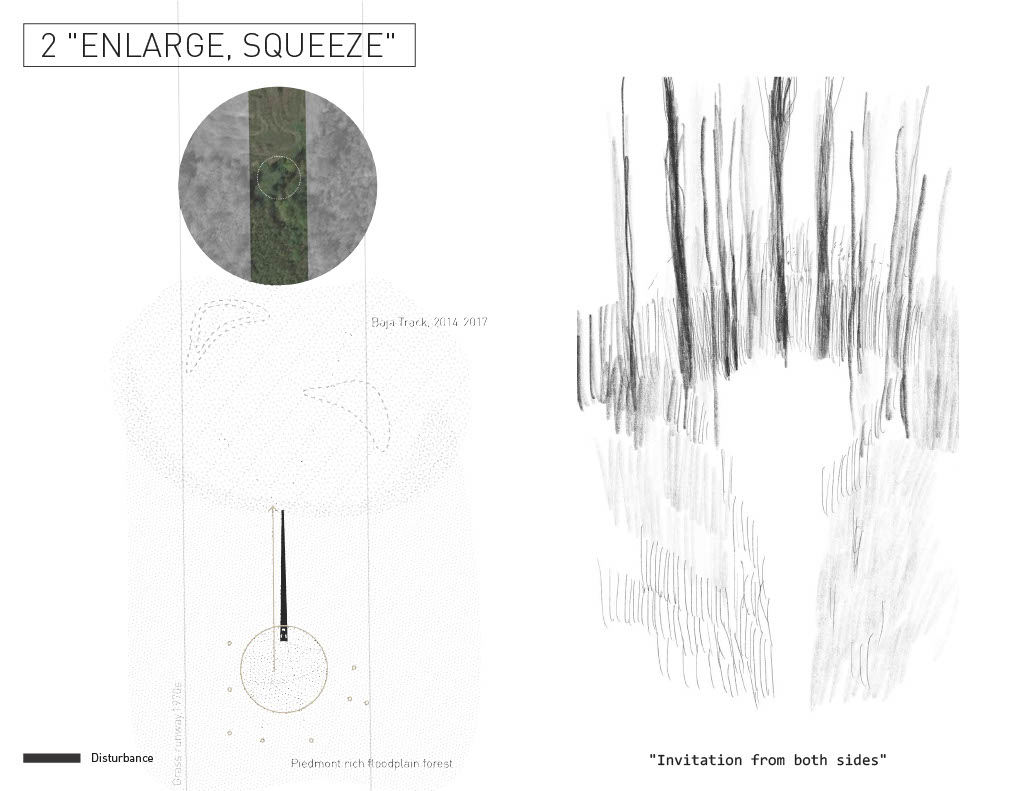

Reading and Registering Palimpsests of Disturbance

LANDSCAPE MARKING

Positioning: How do we recognize and describe a space?

With no built structures at Milton, the sky, the soil and various plant communities constitute the space where we walk through and everything that we may observe. When traversing in and out of various plant communities, the ideas of “space” and “spatial feeling” are constantly switching from micro to macro.

The disturbance, either natural or artificial on site, could be interpreted as attractive or unappealing depending on the viewer’s aesthetic reaction. The sudden inconsistency stands out while we view the surroundings as a continuous landscape; Or it blends in as the scale and proximity to the present might be too distant.

Since the visual effect and continuous reactions created by the surrounding environment are influencing the human body’s senses, the definition of space experience is different for everyone. I want to bring in another perspective of viewing the landscape by extracting or inserting elements on site. The distinguished disturbances are implemented with plain geometries which are obviously human. Each site creates its own “room” compared with the larger “wilderness” in Milton. With such artificial arrangements, the characteristics of the site and plants are revealed in a more accessible way for the human body to move through and make concentration to the human eye.

With no built structures at Milton, the sky, the soil and various plant communities constitute the space where we walk through and everything that we may observe. When traversing in and out of various plant communities, the ideas of “space” and “spatial feeling” are constantly switching from micro to macro.

The disturbance, either natural or artificial on site, could be interpreted as attractive or unappealing depending on the viewer’s aesthetic reaction. The sudden inconsistency stands out while we view the surroundings as a continuous landscape; Or it blends in as the scale and proximity to the present might be too distant.

Since the visual effect and continuous reactions created by the surrounding environment are influencing the human body’s senses, the definition of space experience is different for everyone. I want to bring in another perspective of viewing the landscape by extracting or inserting elements on site. The distinguished disturbances are implemented with plain geometries which are obviously human. Each site creates its own “room” compared with the larger “wilderness” in Milton. With such artificial arrangements, the characteristics of the site and plants are revealed in a more accessible way for the human body to move through and make concentration to the human eye.