Linnea Laux

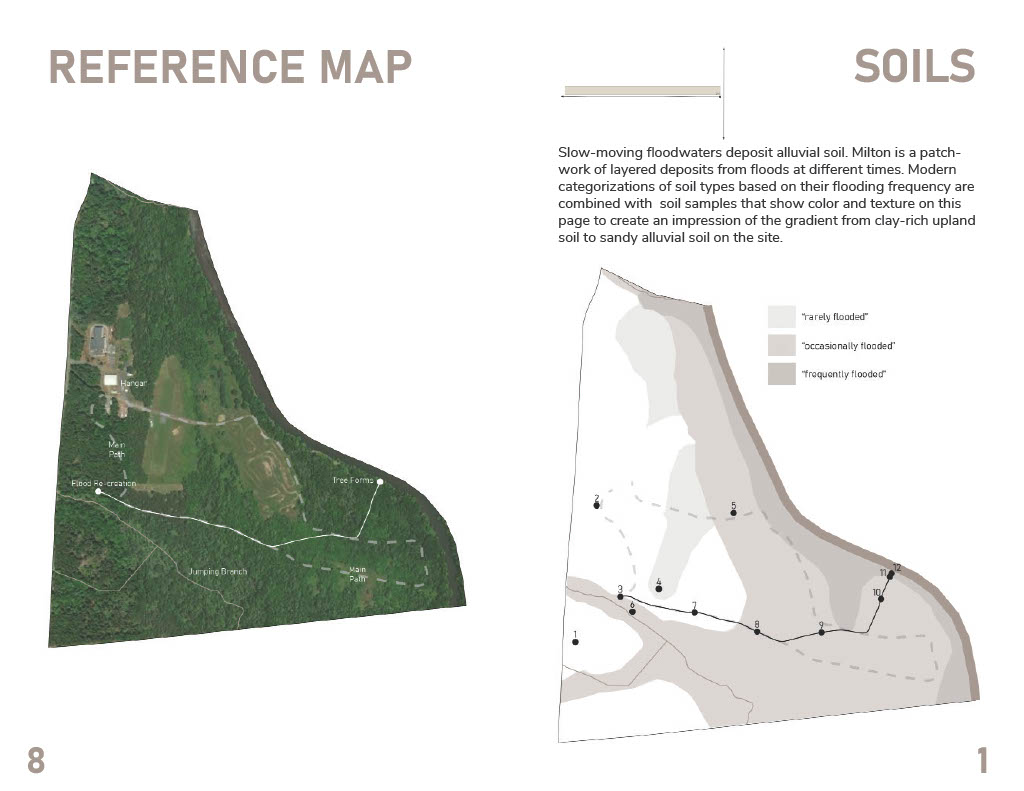

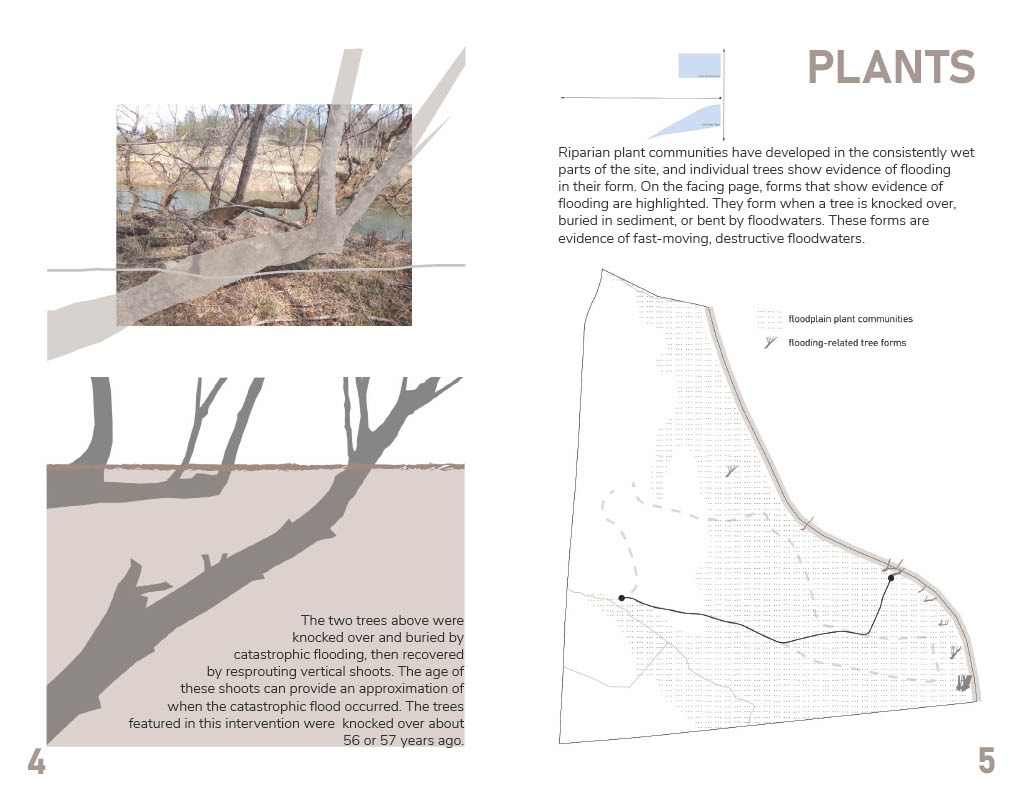

On the first day of class, Matthew showed us a map of Milton with only an aerial and the 100-year floodplain line. I was immediately curious about this line, and whether it could be felt when moving through the landscape. I started to explore changes in soil through Correspondence 1, built little dams on the streams in Correspondence 2, tried to characterize the microtopography at the meeting point of the streams in Correspondence 3, and then settled on exploring alternative sources of evidence about flooding in correspondences 4 and 5. I was limited to the sources of information I could access with my tools and skills, but was still able to map and synthesize botanical, soil, and historical information about flooding. I probably explored ten ideas for literalizing this information in the landscape, but finally settled on painting trees to show their flooded forms, using rope and bungee cord to re-create the water level of a past flood, and putting soil swatches keyed to a map in a booklet to demonstrate the variety of upland and riparian soils on the site.

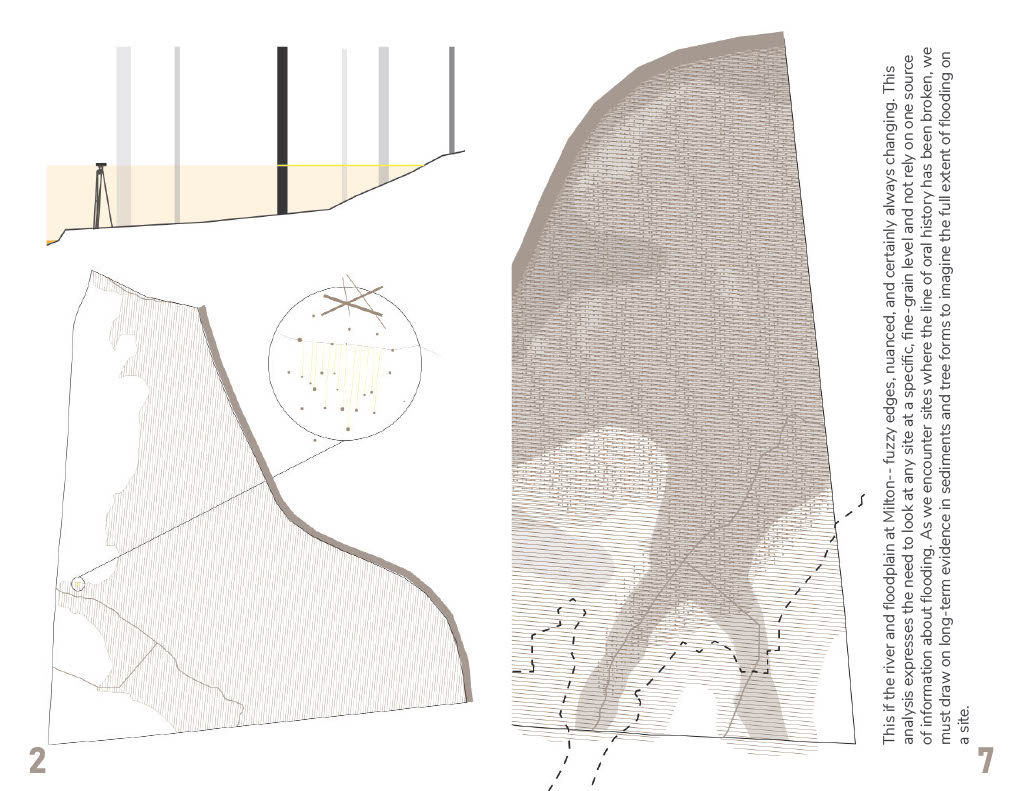

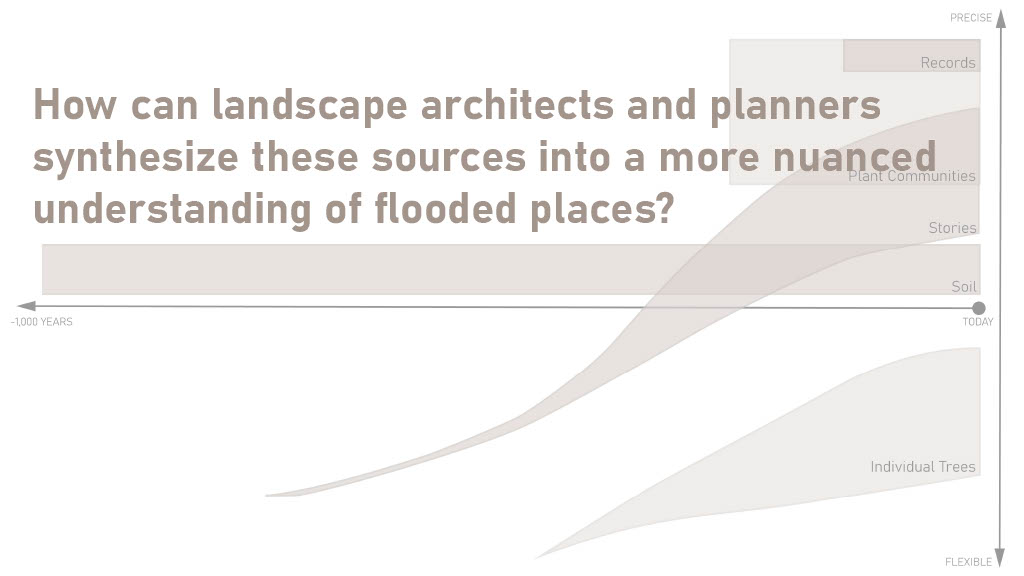

My project essentially explores multiple “ways of knowing” about flooding at Milton. I had expected to be comparing evidence from plants and plant communities, stories, and soil to the historical record, but I found that the record is much spottier than expected. Continuous data is available for less than the past year, and past gauge measurements mainly focus on flood events. My project ended up being a synthesis of botanical, soil, and historical evidence of flooding.

I think that a lot of our ill-advised decisions around “flood control” in the United States stem from the way that we imagine water, land, and floodplains. We create, both through lines on maps and built interventions such as levees, “safe” and “unsafe” zones that are mostly binary and do not change over time. At the same time, we have lost (murdered) or ignored a lot of the ancestral knowledge that could have helped us make better decisions at a local level. Many people and designers live and work in places where they do not have family history. How can they quickly gain an intuition for flooding, and communicate that to others, even without automatic access to an oral tradition? The 100-year floodplain will continue to exist and affect insurance and regulations, but it should not be our first or only source of information about where water may go in the future. Modeling, storytelling, and observation of the evidence on a site must be synthesized to create a nuanced understanding of a flooded place.

My project essentially explores multiple “ways of knowing” about flooding at Milton. I had expected to be comparing evidence from plants and plant communities, stories, and soil to the historical record, but I found that the record is much spottier than expected. Continuous data is available for less than the past year, and past gauge measurements mainly focus on flood events. My project ended up being a synthesis of botanical, soil, and historical evidence of flooding.

I think that a lot of our ill-advised decisions around “flood control” in the United States stem from the way that we imagine water, land, and floodplains. We create, both through lines on maps and built interventions such as levees, “safe” and “unsafe” zones that are mostly binary and do not change over time. At the same time, we have lost (murdered) or ignored a lot of the ancestral knowledge that could have helped us make better decisions at a local level. Many people and designers live and work in places where they do not have family history. How can they quickly gain an intuition for flooding, and communicate that to others, even without automatic access to an oral tradition? The 100-year floodplain will continue to exist and affect insurance and regulations, but it should not be our first or only source of information about where water may go in the future. Modeling, storytelling, and observation of the evidence on a site must be synthesized to create a nuanced understanding of a flooded place.