PLANT MATERIAL

Seed Bank and Propagation at the Milton Land Lab

SP23 Independent Study - Chris Porter (MLA ‘23)propagation noun

: The act or action of propagating: such as

a: to increase (as of a kind of organism) in numbers

b: to spread something (such as a belief)

^ EcoTech IV students seeding flats in early spring

^ EcoTech IV students seeding flats in early spring> Common yarrow (Achillea millefolium var. borealis)

project satement:

PLANT MATERIAL positions seed collection and propagation as invaluable tools for landscape architects. Collecting, storing, and cultivating plants from seed and cuttings are not only essential processes for site-specific restoration and the conservation of local genotypes, but also offer unique opportunities to observe and interact with a site as a full and living medium. The goals of this pilot study are to (1) establish a Milton Seed Bank as a resource for future use by student and faculty researchers and (2) collect the resources + materials and begin a process of local genotype propagation at Milton. Looking forward, this study envisions on-going cycles of seed saving and propagation at the Milton Land Lab as a resource for landscape education and site stewardship.

CONTENTS

the Log: What’s in the seed bank and what’s in the flats?BACKGROUND

01. In-situ propagation vs. conventional plant sourcing

02. Propagation as a tool for stewardship

03. What are local genotypes?

PROPAGATION GUIDE

04. Basic collection + storage + propagation method

COLLECTING SEEDS

SEED BANK PROCESSING + STORAGE

TREATMENT + SEEDING

CARE

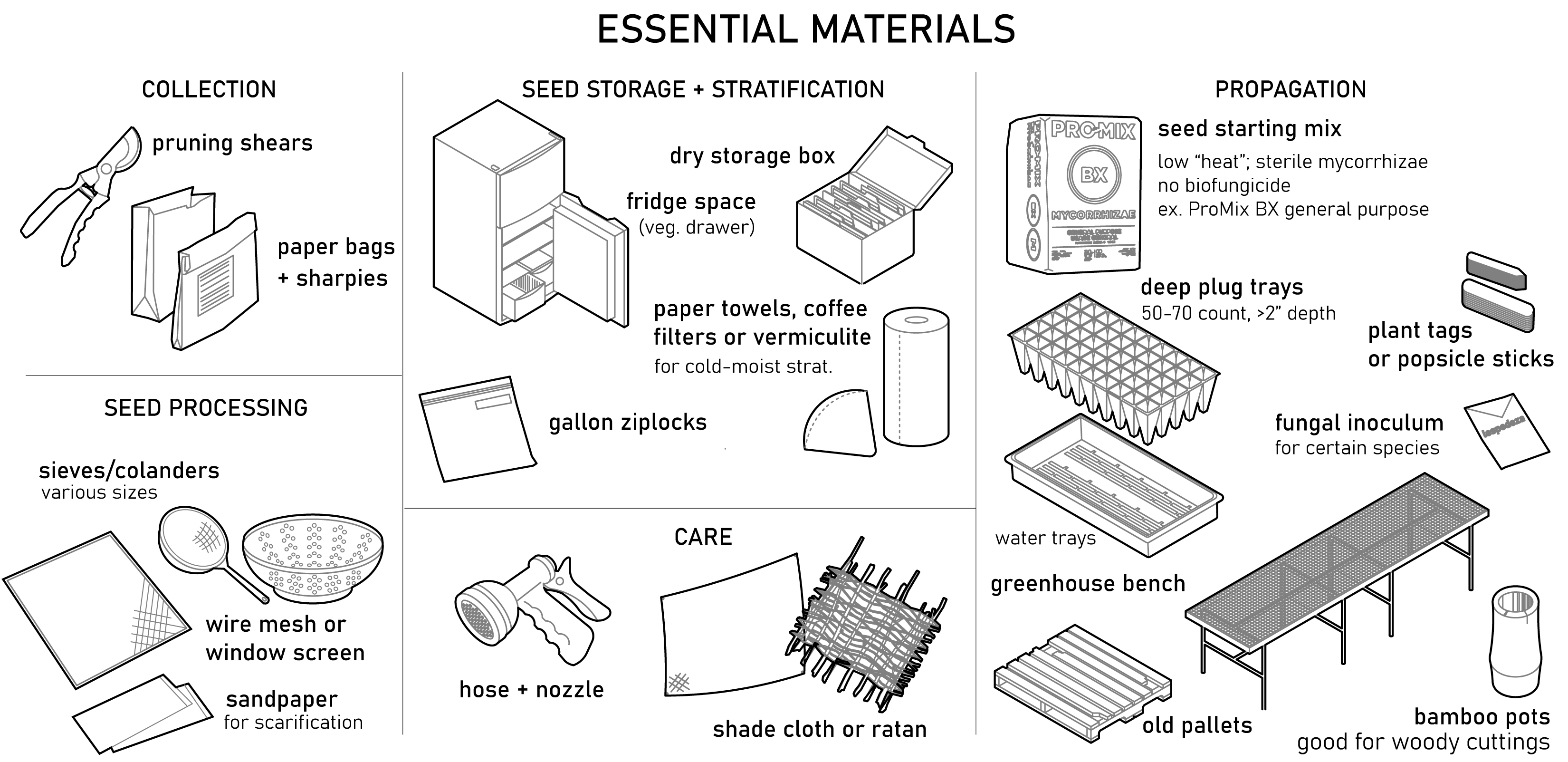

05. Graphic: Essential Materials

06. Graphic: Siting

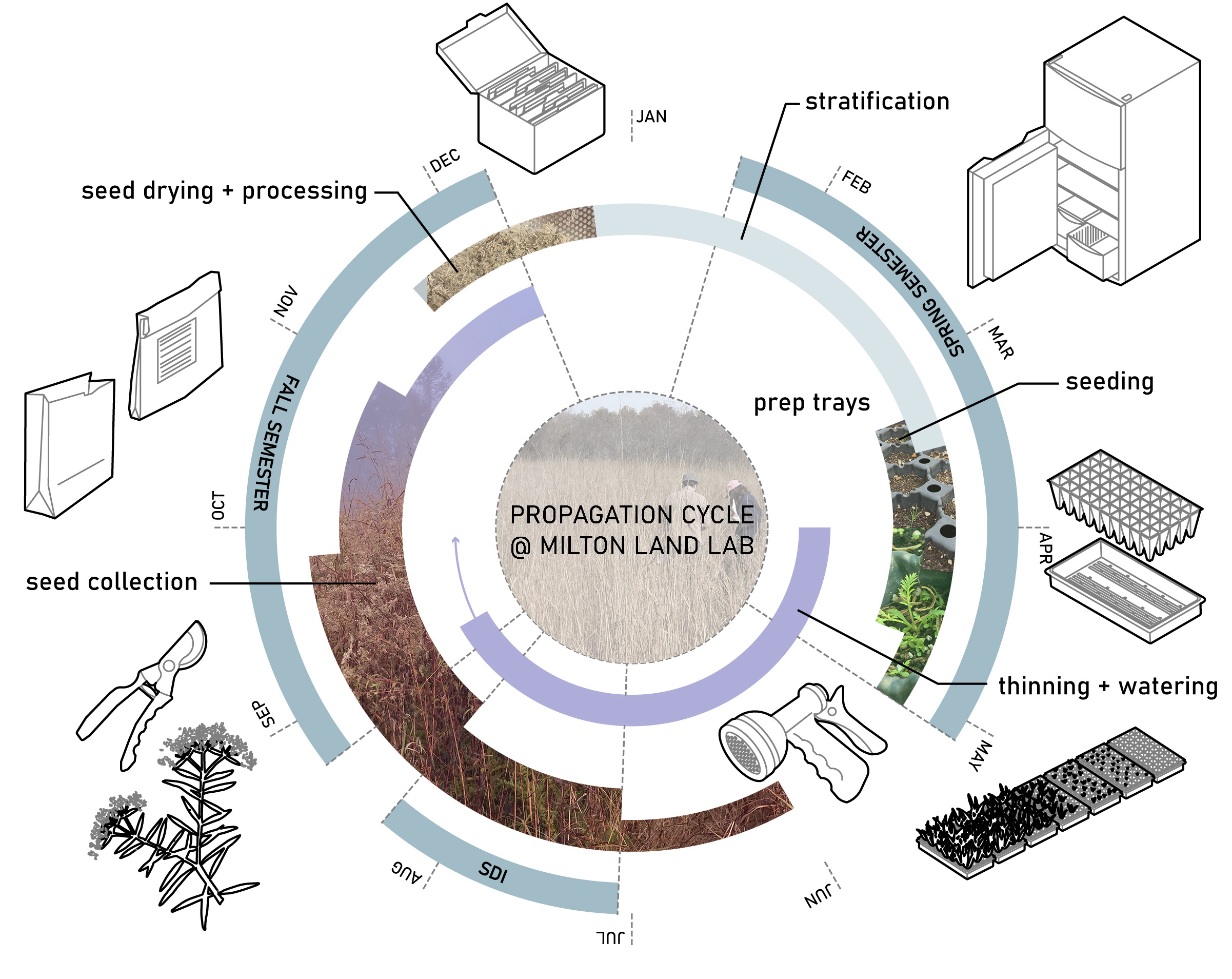

07. Graphic: Seasonal Cycles

08. Looking ahead and Next Steps

BACKGROUND

01. In-situ propagation versus conventional sourcing of “plant material” - the case for landscape architects

Conventional landscape and horticultural projects typically rely on “plant material” purchased from large-scale plant nurseries. These nurseries have tremendous expertise and effectiveness in what they do, but also major limitations. In the mass-production of plants, nurseries tend to propagate individuals with low genotypic diversity: often a small number of nursery-bred “varietals” dominate in nurseries across the country. These varietals are often selected for traits like easy germination, attractive form, fast growth, and tolerance of nursery conditions and transport. Often, traits selected for nursery production or ornamental use - like flower color, bloom time, or seed dormancy - directly compete with traits that help make plants well-adapted to non-horticultural landscapes, native pollinators, and natural disturbances. The result is that in many cases the “native species” available at conventional nurseries have in fact traveled long distances - geographically and genetically - from the species found growing locally in natural plant communities.

But beyond conserving genetic diversity and site-specific fitness, in-situ propagation also has other important benefits for landscape architecture and land stewardship in general: By sourcing plant material from within a site, seed collection and propagation promotes a way of reading and responding to existing site conditions as full and seeing existing plant communities as a resource for regenerative management. In its methods, cycles, trial and errors, propagating plants also offers a way to develop deeper understanding of plants as individual species - their life histories, particular environmental niches, and ecological relationships - and to engage with them across various seasons and life stages.

02. propagation as a tool for stewardship

Propagation from seed is one of many ways to steward and cultivate existing natural plant communities. When performed successfully, seed collection and propagation of native plants can be used to not only increase the number of individuals of a target species, but also enhance community resilience to long-term disturbance and create a resource for conservation and restoration efforts across a site for other sites in the region. Seed collecting and propagation should not seek to negatively impact or supplant the natural regeneration and self-seeding of communities in situ. Rather, its goals are tied to specific conservation, restoration, and landscape stewardship goals:

- To develop a seed bank as a long-term resource for local stewardship

- To propagate plants that can then be transplanted to specific sites where natural self-seeding may be limited or soil has been disturbed

-

To compress or extend dormancy, germination and growth for specific stewardship goals

-

To cultivate plants under more controlled environmental conditions to increase their suitability for a new site

- To exchange genetic material at a regional scale to mitigate habitat fragmentation or assist climate migration

03. What are local genotypes?

“Local genotype” refers to the unique constellation of genetic material present in a plant community growing in a specific place. While we may tend to look at individual plants of a given species as interchangeable, there is often significant genetic diversity within species, across regions, watersheds, and even between two neighboring sites, especially for conservative and rare species. This diversity can reflect adaptations to site-specific environmental conditions, relationships with specific pollinators, other plants, and fungal communities, and even the unique traces of human cultivation or management of that site. In short, local genotypes are communities of plants that are uniquely well-adapted to the place they’re growing. At a larger scale, local genotypes are important reservoirs of genetic diversity that make species resilient to disturbances both locally and globally.

PROPAGATION GUIDE FOR MILTON LAND LAB

04. Basic collection + storage + propagation methods

Methods for propagating plants vary widely based on the unique life cycles and adaptations of each species. For some species, propagation by seed is the most effective method. For others - like woody plants or ferns - propagation by seed/spore is much less efficient than propagation by cuttings or division. Understanding the appropriate propagation methods for each species reinforces an understanding of their unique growth habits, environmental niches, and ecological relationships.

For many of the upland Piedmont prairie species found at Milton, propagation from seed can usually be achieved in single year - collecting seeds in the late summer and fall, drying and processing them, and stratifying species over the winter outside or in the fridge. Most species will begin to germinate in early spring with warmer temperatures and sunlight. Many of these species being wind-dispersed heliophytes, they germinate relatively easily after stratification and can tolerate minimal watering in well-sited plug trays. The resulting plugs are usually well suited for transplating after 1 or 2 seasons.

COLLECTING SEEDS

Most of the upland prairie species at Milton flower between July and October and have mature seedheads from October through December; November is a good time to bulk collect seeds from a variety of grassland species, including the major grasses, but other collection windows should be considered for early-flowering species, fruit trees, etc.

When collecting seeds, seek to:

(1) avoid negatively impacting the natural self-seeding of the prairie by harvesting no more than 25-50% of seeds from individual plants and areas,

(2) collect “wide and shallow” from multiple individuals and areas to minimize impact and maximize genetic diversity,

(3) use pruning shears/scissors to cut seed heads to avoid damaging or uprooting living plants

(4) keep good documentation directly on seed collection bag, including species name, collection date, collection site + area of site or approximate coordinates, and your initials

^collecting narrow leaf mountain mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium) seed heads with pruning shears

^collecting narrow leaf mountain mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium) seed heads with pruning shears

^paper collection bags

^paper collection bags ^ seeds collected from 14 species in ~30 minutes by EcoTech III students

^ seeds collected from 14 species in ~30 minutes by EcoTech III students  ^suckers collected from American plum (Prunus americana) for propagation by cutting

^suckers collected from American plum (Prunus americana) for propagation by cuttingSEED BANK PROCESSING + STORAGE

Once seeds have been collected, they should be allowed to dry in paper bags for a week or more. After that, proper processing of the seeds is essential to enhance germination success and increase the “shelf life” of the seed bank.

In general, the intention is to remove all non-seed material (petals, leaves, stems, duff, dirt) and isolate the seeds. This decreases the risk of mold. For some species, isolating the seeds can be as simple as shaking the bag once the inflorescences have dried, allowing the seeds to collect at the bottom. For others (especially wind-dispersed seeds with a lot of “fluff”), it may require rubbing the inflorescences against a colander or sieve to filter out the seeds.

Once seeds are isolated, they can be stored in a paper bag in a dry, dark place or in the fridge, being sure to carry over all the initial collection information.

^ Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) pod; scale-like seeds are carried by tufts of white “silk”

^ Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) pod; scale-like seeds are carried by tufts of white “silk”  ^isolating splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternarius) seeds using colander

^isolating splitbeard bluestem (Andropogon ternarius) seeds using colander

^ seeds from narrow leaf mountain mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium) seperated at bottom of paper bag

^seed bags after being processed, stored in flat dry bags; box can be kept in dry, dark place or fridge for long-term storage

^seed bags after being processed, stored in flat dry bags; box can be kept in dry, dark place or fridge for long-term storageTREATMENT + SEEDING

Unlike domesticated vegetables or herbs - which have generally been bred to germinate quickly and easily - the seeds of many native grassland species have mechanisms that inhibit germination until conditions are ideal for growth. In some cases, we can artificially reproduce the conditions to speed up the timeline: a few weeks in the fridge can simulate winter stratification, while scarification with steel wool or sandpaper can break down outer shells that would otherwise have to be chewed by animals or slowly broken down in the soil.

The log document records species-specific propagation information using the following codes:

(adapted from Prairie Moon Nursery germination codes)

A - Easiest propagaters - just direct sow in early spring

C(x) - Requires cold or cold-moist stratification for (x) days - Can be achieved by sowing outside in flats in the fall or placing in ziplocks in the fridge with moist a paper towel

D - Seeds need light to germinate - must be surface sown and may require good springtime light (ex. narrow leaf mountain mint)

E - warm-moist + cold-moist period - i.e. seeds naturally wait +1 year to germinate; This can be achieved more quickly using hot water soaking + fridge stratification, or flats can just be left out to naturally germinate after one 1 year.

H - scarification - outer hull prevents germination (in nature, seeds might be chewed or digested by animals or slowly broken down in the soil) - requires scarification using sandpaper, wire mesh or steel wool

I - legume; rhizobium inoculum - has obligatory symbiotic fungal relationship; since seed-starting mix is generally sterile, genus-specific inoculum must be added (they can be purchased online from Prairie Moon, or even cultivated from existing soils)

^ Autumn bentgrass (Agrostis perennans) seeds on moist paper towel for cold-moist stratification

^ Autumn bentgrass (Agrostis perennans) seeds on moist paper towel for cold-moist stratification ^cold-most stratification bags in vegetable drawer

^cold-most stratification bags in vegetable drawer ^Eastern gama grass (Tripsacum dactyloides) seeds before being scarified using sandpaper

^Eastern gama grass (Tripsacum dactyloides) seeds before being scarified using sandpaper ^Flats sown in Dec for over-winter outdoor stratification

^Flats sown in Dec for over-winter outdoor stratification ^Flats are labeled with number (recorded in log), species, planting date, and initials (on reverse side)

^Flats are labeled with number (recorded in log), species, planting date, and initials (on reverse side)CARE

After seeding, plants will (hopefully) begin to germinate in the early spring, but will require observation and care on a regular basis throughout the spring and summer.

Once the last frost is past, flats should be moved to an area with dappled shade and protection from wind. Most species should be kept out of full direct sun for a least their first summer of growth. For heliophyte species, it isn’t essential to keeping the soil moist all the time, but flats on a raised bench will still dry out much more quickly than natural soils - Placing thick cardboard or plywood underneath flats to slow water loss and can help to reduce watering needs in the spring to 1-2 times per week, as needed to supplement natural rainfall. Woodland species will require more regular watering and deeper shade; For riparian/wetland species, a shallow tray with a consistent inch of water in it can be used.

The early spring is slow on activity, but observe the flats regularly for germination; For many species - like narrow-leaf mountain mint - the seedlings are extremely small, so look closely! Record the approximate dates of earliest germination for future reference. Keep the flats clear of large debris (tulip poplar flowers and maple samaras and especially annoying) to allow sunlight to reach surface-sown seedlings. One of the initial learning curves is learning to identify species by their early cotyledons and distinguish them from weeds: maple seedlings and henbit were the two regular weeds found in my flats.

Once seedlings develop secondary leaves and start to reach a recognizable size, over-seeded cells may need to be thinned by carefully raking soil around edge of cells or cutting/plucking seedlings with your fingers. Thinning at the right time can help to induce more rapid growth, similar to transplating.

Long-term, plugs may benefit from light nutrient additions such as compost tea, but be cautious as some prairie species may respond negatively to being over-fertilized. In general, native prairie species should be fairly “hands off” once they are well established in the plugs. Keep an eye out for slugs (the raised bench helps) and squirrels, who may decide to replace your seedlings with acorns.

05. Essential Materials

06. Siting

07. Seasonal Cycles

08. Looking ahead and Next Steps

The timeline of native plant propagation extends far beyond a single academic semester, and this single cycle of seed collection and propagation is a small pilot study for what hopefully becomes a larger and continual project to be taken up and reimagined by future courses and cohorts.

Using these supplies and this basic methodoloy, cycles of seed saving and nursey-style propagation could continue at the Milton Land Lab into the future. At the same time, many other trajectories or ways of propagating existing plant material could be imagined: “seed bombs”, mixed-species flats, direct-sow test plots at Milton, or even custom-fabricated seed trays are all ideas that could be tested by future classes and student researchers building on this base.

Even for the seeds and plants collected and grown in this first season, many questions remain: How successfully will the seed bank continue to be managed and expanded? When these plugs eventually reach transplantable size, where should they go? What other projects - at Milton or elsewhere - could use these seeds or plugs in the future? What other materials and infrastructure (tables, shade structures, a greenhouse?) could help facilitate more propagation activity and experiments?

In conclusion, this study hopes to be a first step in what could be a long-term relationship with propagation at the Milton Land Lab as an educational tool, a resource for future projects, and the stewardship of Milton’s natural plant communities into the future.